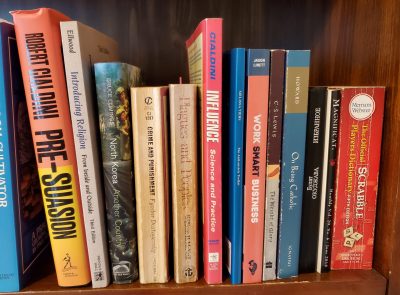

Commas are, without a doubt, the punctuation mark that gives everyone the most headaches. One reason is that they are the most frequently used of all punctuation. A few days ago, as I was preparing for this latest installment in our punctuation series, I decided to conduct my own informal survey. I selected five books at random from our personal library, and five pages within each book—so 25 pages in all. It turned out that there were only 4 pages out of those 25 in which the comma was not the highest frequency mark; the period overtook it in all of those. And in all five books, the average of the five sampled pages always came out with the comma as the winner.

Another cause of comma confusion is that in some places you need it, but in others it’s optional. (Does that remind you of the semicolon from last time around?) And there are many contexts where commas should or can be used: the section on the comma in the Chicago Manual of Style runs 37 paragraphs! Compare that to the period, which Chicago covers in just four paragraphs. But relax—we’re going to take the comma step by step, starting out with its most clear-cut uses and gradually working up to more complicated ones. (And no way are we going to cover all 37 paragraphs!)

I think most of us learned in school that a comma indicates a pause in a sentence, as opposed to a period’s full stop. If a period is a stop sign, you could think of a comma as a yield.

This analogy will be helpful especially when we get to the more complex uses of the comma. Just as you wouldn’t want too many yield signs in one short stretch of road, you don’t want to overload your sentences with commas, which could make your writing jerky. Yet you want enough to manage the flow of your traffic, er, sentences properly. The end goal, as with everything in your writing, should always be to make your meaning clear and easy to read.

All the uses of that comma that we’ll look at today are mandatory.

One of the most basic is the commas in pairs rule: whenever a comma sets off an element such as the year in a date or the name of a state or country after a city, there must be another comma following that element:

After conducting the informal punctuation survey on May 28, 2020, I began writing the blog post.

The yield sign picture was taken in Orlando, Florida, in the neighborhood where I live.

You also need a comma when you want to join two independent clauses with a conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so). Remember that “independent clause” is just another name for a complete sentence, which has a subject (an actor) and a verb (an action or a linking verb). So you could take two sentences such as:

Some drivers almost come to a stop at yield signs. Others hardly slow down at all.

…and make them one:

Some drivers almost come to a stop at yield signs, but others hardly slow down at all.

The important points to remember are that you must be joining two independent clauses, and you need both the comma and the conjunction. If you leave out the conjunction, you have the error called a “comma splice”:

Incorrect version of the above example: Some drivers almost come to a stop at yield signs, others hardly slow down at all.

Just as you might have heard of the “comma splice,” maybe you’ve encountered the term “Oxford comma.” It sounds fancy, but it’s simply this: when listing three or elements in a series, with a conjunction before the last one, there should be a comma between all the elements and before the conjunction. This is also known as the serial comma rule, and here’s what it looks like:

Among the books I sampled were a novel, a history book, and a business book.

You could argue that this is our first optional use of the comma, because some style guides do not require the last comma before the conjunction—which would look like this:

Among the books I sampled were a novel, a history book and a business book.

However, I agree with The Chicago Manual of Style that consistently using the serial comma prevents misunderstanding. What if you had a sentence like this:

The authors included collaborating academicians, Cialdini, and Dostoevsky.

This sentence that includes the serial comma is clear that we’re talking about three separate entities: 1) the group of academicians, 2) Cialdini, and 3) Dostoevsky. But if you omit the final comma after Cialdini, you get:

The authors included collaborating academicians, Cialdini and Dostoevsky.

This version could be interpreted to mean that the names of the collaborating academicians are Cialdini and Dostoevsky—just two entities, in other words. So using the serial comma keeps everything clear.

Finally for today we have the use of the comma between two or more adjectives (descriptive words) before a noun. Sometimes you need it; sometimes you don’t. But don’t worry—there are two tests to help you figure this out: if you can put the word and between the adjectives and the sentence still makes sense, then you need a comma between them. Or, if you can reverse or rearrange the order of the adjectives and the sentence still makes sense, then again, put a comma between them:

Cialdini’s Influence is an interesting, accessible book.

If you run the tests, you get the following, both of which make sense—so a comma goes between interesting and accessible:

Using and instead of a comma: Cialdini’s Influence is an interesting and accessible book.

Reversing the order: Cialdini’s Influence is an accessible, interesting book.

And again:

Crime and Punishment has a complex, detailed plot.

Apply the tests—again, this one passes, so it needs the comma:

Using and instead of a comma: Crime and Punishment has a complex and detailed plot.

Reversing the order: Crime and Punishment has a detailed, complex plot.

Here are some sentences that don’t pass the tests, so no comma goes between the adjectives:

Dostoevsky is considered one of the masters of nineteenth-century Russian literature.

Try the tests—compare how they don’t work here the way they did above—so no comma:

Using and instead of a comma: Dostoevsky is considered one of the masters of nineteenth-century and Russian literature.

Reversing the order: Dostoevsky is considered one of the masters of Russian nineteenth-century literature.

And again:

We have many yield signs in our town to control the heavy neighborhood traffic.

Try the tests:

Using and instead of a comma: We have many yield signs in our town to control the heavy and neighborhood traffic.

Reversing the order: We have many yield signs in our town to control the neighborhood heavy traffic.

This sentence clearly fails test number one. The result of test number two isn’t bad, but it doesn’t sound as natural as the original version. At any rate, since it definitely failed one test, no comma here.

Whew, I think that’s quite enough for one day! Take some time over the next two weeks to start looking for places in your writing that would require these rules, and be on the lookout for examples “in the wild.” A good way to master these rules is to focus on just one for several days; when you feel you’re getting more confident applying it, add another. If you have any questions, please feel free to leave a comment below. I’ll be back soon to unravel more mysteries of the comma!