One of the surprising side effects of the COVID-19 pandemic has been an increased demand for cybersecurity experts. It seems every time you turn on the TV lately, there are plenty of commercials offering programs to teach jobseekers these skills. Since we’re all online so much now—for work, shopping, and just staying in touch with each other—there’s increased risk of our personal data being stolen.

Have you ever stopped to think about what goes into that personal data? Just what information is essential to identify you as an individual? How about these: your full name; your birthday; credit card numbers; your Social Security number, for you Americans out there—the list is extensive, and even depends on the part of the word you live in.

But then there are other facts about you that, while interesting and maybe even important, are true of many people: that you live in a particular town or city; that you play a particular sport; that you have a dog or cat for a pet, and so on. This type of information doesn’t single you out; you could call it extra information.

In today’s installment of our continuing series on comma usage, let’s take a look at how these types of information—essential and extra—are handled in sentences.

With relative clauses:

A relative clause is a phrase within a sentence that modifies a noun and starts with that, which, or who/whom/whose. Sometimes a relative clause contains information essential to identifying a specific person or thing, but other times it contains extra information. For example:

When we visited the mother dog and her litter, we decided to take the puppy who had a white spot on her chest.

Our puppy, who has a white spot on her chest, loves to play fetch.

Notice how in the first example, the relative clause who had a white spot on her chest is essential for identifying which puppy we selected. If you got rid of that clause, the remaining sentence wouldn’t make any sense: *When we visited the dog and her litter, we decided to take the puppy. This leaves the reader wondering which puppy we picked. (BTW, the asterisk before the sentence means that it’s ungrammatical.)

In the second sentence, however, since we don’t have to single out a particular puppy, you could leave out the relative clause who has a white spot on her chest and the sentence would still make sense: Our puppy loves to play fetch. In this case, the clause who has a white spot on her chest is extra information.

Traditionally, grammarians have called the essential type “restrictive” and the extra type “non-restrictive.” But I’ve never found those terms helpful, so I’m going to stick with these concepts of essential and extra information throughout this post.

Now, on to the role of the comma. Look again at the essential example:

When we visited the mother dog and her litter, we decided to take the puppy who had a white spot on her chest.

Note that there is no comma before who. But in the extra example:

Our puppy, who has a white spot on her chest, loves to play fetch.

There are commas around the clause who has a white spot on her chest. So the rule is: if the relative clause contains essential information, it does not take commas; but if the relative clause contains extra information, it does take commas.

Another way to look at it is that the commas are functioning almost like parentheses—they are signposts that mean “We don’t need this information to identify someone or something.”

One more example:

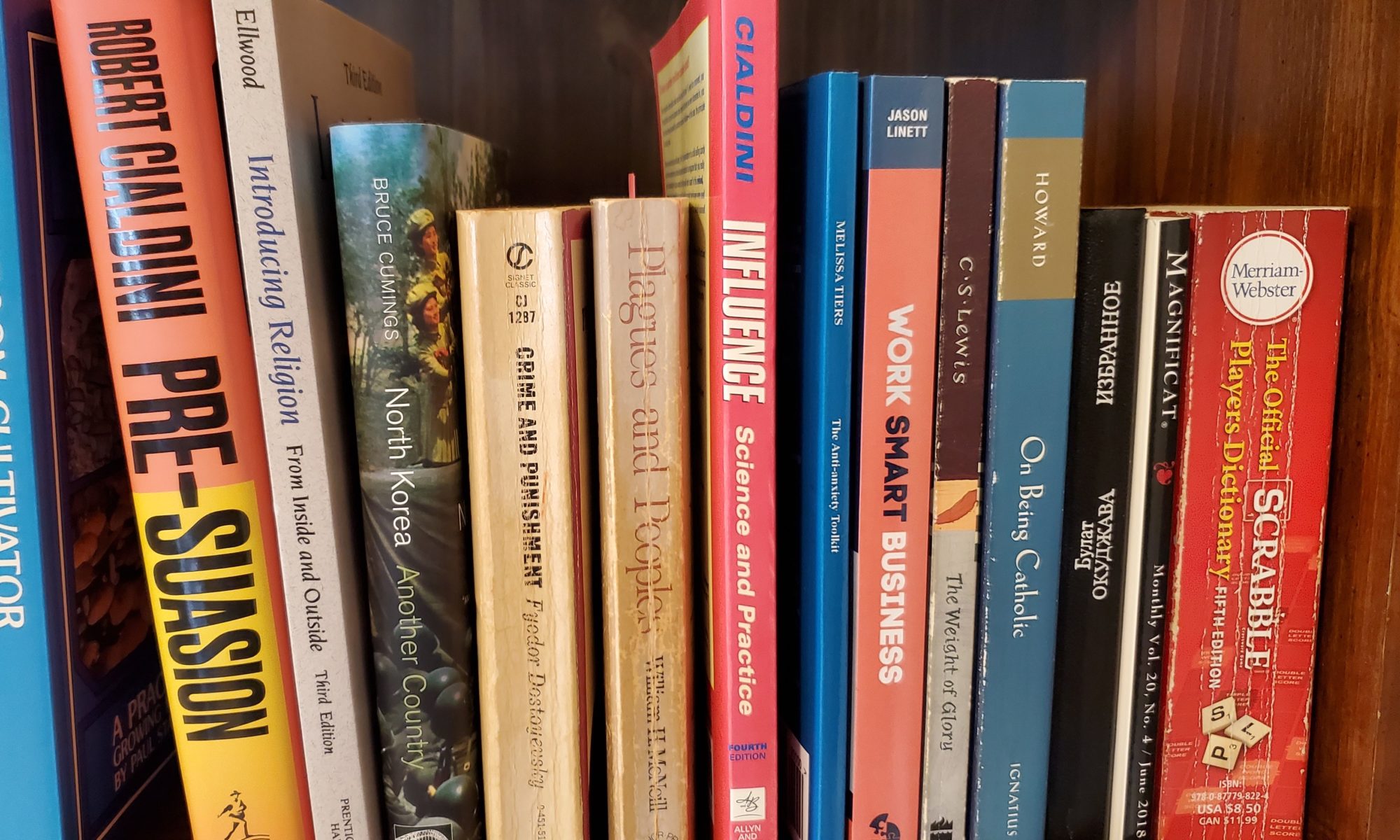

Every book that Chuck owns is about sports.

The book The Boys of Summer, which Chuck owns, details the history of the early 1950s Brooklyn Dodgers.

If we remove the essential relative clause that Chuck owns from the first sentence, we’d be left with Every book is about sports. And of course that’s not true. Notice that there are no commas, either.

But we can remove the extra relative clause—everything between the commas—from the second and it’s still a true statement: The book The Boys of Summer details the history of the early 1950s Brooklyn Dodgers. The fact that Chuck has a copy of this book is extra information.

You’ve no doubt noticed that in the first sentence the word that starts off the relative clause, but in the second it’s which. You’ll come across some traditional grammars that prescribe using that only with essential clauses, and which only with extra clauses. But this is not actually a hard and fast rule. Native speakers of English tend to automatically use that only with essential clauses, but you can use which with either type. Just go with whichever sounds better to your ear, and then check whether you need to have commas (extra) or not (essential). Chances are that if you naturally used that, it will be an essential clause, which does not need the commas.

With appositives:

Whew! I know that was a lot to absorb. But fortunately this next rule works just like the one for relative clauses.

First of all, what’s an appositive? It’s a word or phrase which usually follows directly after a noun and provides more information about that noun—for example:

Jason’s wife, Helga, is a German citizen.

Here Helga is an appositive to—more information about—Jason’s wife.

Do you see where we’re going with this? If an appositive provides more information about a noun, sometimes that information is going to be—you guessed it—essential, and other times it’s going to be extra. And the comma rules are exactly the same as with relative clauses: no commas with essential information; commas (again, think parentheses) with extra information.

So why did we use commas in that example? Jason has only one wife, so we don’t need her name to single her out. It’s extra information. But how about this one:

Jenn’s brother Nate came to visit her.

No commas here—which means that Jenn has more than one brother; Nate is the one who came to visit, and his name is essential in order to pinpoint him. But what if the sentence had been written this way:

Jenn’s brother, Nate, came to visit her.

At first glance this seems to be the exact same sentence. But check out the commas—this version means that Jenn has only one brother, so his name is extra information.

One more set of examples, this one not so tricky:

Many theater lovers consider Shakespeare’s play Hamlet the greatest drama of all time.

Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio, is not often performed.

In the first sentence, Hamlet is essential to identify which one of Shakespeare’s plays we’re talking about—so no commas. But in the second sentence, since Beethoven wrote only one opera, the name isn’t essential—it’s extra information.

By now your head is probably spinning—mine certainly was when I first started paying attention to this distinction. And you might even wonder why it matters. I have no answer for that, other than to say that it does: observing the rules and correctly applying (or not applying) the commas will distinguish you as a careful writer who pays attention to detail.

And some good news—this is the most subtle, most difficult application of all of the comma rules. You’ve seen the worst now, so our last installment on the comma will be a piece of cake! I’ll be back soon with those few remaining rules. Until then, as always, look for these principles at work “in the wild,” and practice using them in your own writing. And please feel free to leave any questions below!

)

)