|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Commas are, without a doubt, the punctuation mark that gives everyone the most headaches. One reason is that they are the most frequently used of all punctuation. A few days ago, as I was preparing for this latest installment in our punctuation series, I decided to conduct my own informal survey. I selected five books at random from our personal library, and five pages within each book—so 25 pages in all. It turned out that there were only 4 pages out of those 25 in which the comma was not the highest frequency mark; the period overtook it in all of those. And in all five books, the average of the five sampled pages always came out with the comma as the winner.

Another cause of comma confusion is that in some places you need it, but in others it’s optional. (Does that remind you of the semicolon from last time around?) And there are many contexts where commas should or can be used: the section on the comma in the Chicago Manual of Style runs 37 paragraphs! Compare that to the period, which Chicago covers in just four paragraphs. But relax—we’re going to take the comma step by step, starting out with its most clear-cut uses and gradually working up to more complicated ones. (And no way are we going to cover all 37 paragraphs!)

I think most of us learned in school that a comma indicates a pause in a sentence, as opposed to a period’s full stop. If a period is a stop sign, you could think of a comma as a yield.

This analogy will be helpful especially when we get to the more complex uses of the comma. Just as you wouldn’t want too many yield signs in one short stretch of road, you don’t want to overload your sentences with commas, which could make your writing jerky. Yet you want enough to manage the flow of your traffic, er, sentences properly. The end goal, as with everything in your writing, should always be to make your meaning clear and easy to read.

All the uses of that comma that we’ll look at today are mandatory.

One of the most basic is the commas in pairs rule: whenever a comma sets off an element such as the year in a date or the name of a state or country after a city, there must be another comma following that element:

After conducting the informal punctuation survey on May 28, 2020, I began writing the blog post.

The yield sign picture was taken in Orlando, Florida, in the neighborhood where I live.

You also need a comma when you want to join two independent clauses with a conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so). Remember that “independent clause” is just another name for a complete sentence, which has a subject (an actor) and a verb (an action or a linking verb). So you could take two sentences such as:

Some drivers almost come to a stop at yield signs. Others hardly slow down at all.

…and make them one:

Some drivers almost come to a stop at yield signs, but others hardly slow down at all.

The important points to remember are that you must be joining two independent clauses, and you need both the comma and the conjunction. If you leave out the conjunction, you have the error called a “comma splice”:

Incorrect version of the above example: Some drivers almost come to a stop at yield signs, others hardly slow down at all.

Just as you might have heard of the “comma splice,” maybe you’ve encountered the term “Oxford comma.” It sounds fancy, but it’s simply this: when listing three or elements in a series, with a conjunction before the last one, there should be a comma between all the elements and before the conjunction. This is also known as the serial comma rule, and here’s what it looks like:

Among the books I sampled were a novel, a history book, and a business book.

You could argue that this is our first optional use of the comma, because some style guides do not require the last comma before the conjunction—which would look like this:

Among the books I sampled were a novel, a history book and a business book.

However, I agree with The Chicago Manual of Style that consistently using the serial comma prevents misunderstanding. What if you had a sentence like this:

The authors included collaborating academicians, Cialdini, and Dostoevsky.

This sentence that includes the serial comma is clear that we’re talking about three separate entities: 1) the group of academicians, 2) Cialdini, and 3) Dostoevsky. But if you omit the final comma after Cialdini, you get:

The authors included collaborating academicians, Cialdini and Dostoevsky.

This version could be interpreted to mean that the names of the collaborating academicians are Cialdini and Dostoevsky—just two entities, in other words. So using the serial comma keeps everything clear.

Finally for today we have the use of the comma between two or more adjectives (descriptive words) before a noun. Sometimes you need it; sometimes you don’t. But don’t worry—there are two tests to help you figure this out: if you can put the word and between the adjectives and the sentence still makes sense, then you need a comma between them. Or, if you can reverse or rearrange the order of the adjectives and the sentence still makes sense, then again, put a comma between them:

Cialdini’s Influence is an interesting, accessible book.

If you run the tests, you get the following, both of which make sense—so a comma goes between interesting and accessible:

Using and instead of a comma: Cialdini’s Influence is an interesting and accessible book.

Reversing the order: Cialdini’s Influence is an accessible, interesting book.

And again:

Crime and Punishment has a complex, detailed plot.

Apply the tests—again, this one passes, so it needs the comma:

Using and instead of a comma: Crime and Punishment has a complex and detailed plot.

Reversing the order: Crime and Punishment has a detailed, complex plot.

Here are some sentences that don’t pass the tests, so no comma goes between the adjectives:

Dostoevsky is considered one of the masters of nineteenth-century Russian literature.

Try the tests—compare how they don’t work here the way they did above—so no comma:

Using and instead of a comma: Dostoevsky is considered one of the masters of nineteenth-century and Russian literature.

Reversing the order: Dostoevsky is considered one of the masters of Russian nineteenth-century literature.

And again:

We have many yield signs in our town to control the heavy neighborhood traffic.

Try the tests:

Using and instead of a comma: We have many yield signs in our town to control the heavy and neighborhood traffic.

Reversing the order: We have many yield signs in our town to control the neighborhood heavy traffic.

This sentence clearly fails test number one. The result of test number two isn’t bad, but it doesn’t sound as natural as the original version. At any rate, since it definitely failed one test, no comma here.

Whew, I think that’s quite enough for one day! Take some time over the next two weeks to start looking for places in your writing that would require these rules, and be on the lookout for examples “in the wild.” A good way to master these rules is to focus on just one for several days; when you feel you’re getting more confident applying it, add another. If you have any questions, please feel free to leave a comment below. I’ll be back soon to unravel more mysteries of the comma!

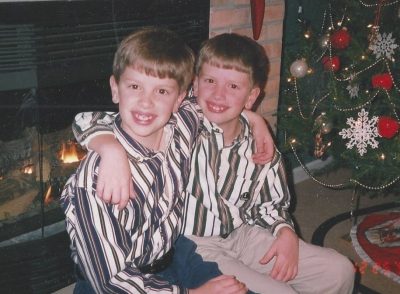

I mentioned previously that my husband and I have sons who are twins, but unfortunately I didn’t have space in that post to talk more about them. They’re grown up now (I can’t believe they’ll be 30 in July!) but raising them was quite an experience. We gave them similar names, and they look a lot alike, though not as much now as when they were kids. Yet despite having many common interests, they have distinctly different personalities.

Which brings us to the latest installment of our punctuation survey: the colon and the semicolon, which would seem to be the twins of the punctuation world. Like our sons, they have similar names. And each is made up of two other punctuation marks: a colon is two periods stacked up, while a semicolon is a period over a comma. But despite the similarities, colons and semicolons are used very differently.

First, a quick grammar definition which will help with the following explanations. Remember that for a string of words to be considered a complete sentence, it needs a subject (an actor) and a verb (an action or a linking word). Another name for a sentence is an independent clause:

Scientific researchers often use identical twins as subjects.

I can’t imagine what it would be like to have triplets or more.

Some cultures consider the birth of twins to be good luck.

Be on the lookout—you might see some of these independent clauses again soon. And now that we have that out of the way, let’s get started.

The easiest way to remember what a colon does it to think of it as meaning “as follows.” You can use one at the end of an independent clause to indicate that the words following will explain, illustrate, or amplify what you said before the colon. The material after the colon can be another sentence or a list:

Scientific researchers often use identical twins as subjects: their matching DNA profiles allow the scientists to control for one variable.

Parents need three attributes for raising twins: flexibility, a positive attitude, and endless patience.

And as a matter of fact, you can even include the words “as follows,” or other such introductory words, before a colon:

I always give new parents of twins the following advice: don’t sweat the small stuff, and remember that most of it is small stuff.

Just one caution with the colon: always remember that it should come after an independent clause—that is, a compete sentence. Don’t use a colon when you have a list within a sentence:

Incorrect: Our sons’ common interests are: languages, video games, and martial arts.

This is incorrect because the bit before the colon—Our sons’ common interests are—is not a complete sentence without a complement after the linking verb are. Here’s how it should look:

Correct: Our sons’ common interests are languages, video games, and martial arts.

While the colon is pretty straightforward, the semicolon can be a bit trickier because its use is often optional. Some writers love it, while others never use it at all. For hardcore grammar nerds (like me) there’s even a whole book about the use and abuse of the semicolon throughout the history of English literature and prose. (I am not an Amazon affiliate and do not receive anything for this endorsement.)

So let’s take it one step at a time. The easiest way to use a semicolon is to join two independent clauses without a joining word (conjunction) when the writer wants to make a close connection between them:

Raising twins wasn’t easy; I can’t imagine what it would be like to have triplets or more.

Identical twins share 100% of their DNA; fraternal twins share just 50%, the same as regular siblings.

In both these cases you can see why the writer would opt to link the independent clauses; they are clearly related. But you could instead join them with a comma and a conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, or so):

Raising twins wasn’t easy, so I can’t imagine what it would be like to have triplets or more.

Identical twins share 100% of their DNA, but fraternal twins share just 50%, the same as regular siblings.

Or you could make them two separate sentences:

Raising twins wasn’t easy. I can’t imagine what it would be like to have triplets or more.

Identical twins share 100% of their DNA. Fraternal twins share just 50%, the same as regular siblings.

So this is a stylistic choice. All these options are grammatically acceptable, but each has a different feel to it. To me, the last option—making them two sentences—seems choppy. But sometimes that might be the effect you want to create.

You can also include an introductory word or phrase after the semicolon and before the second sentence. Words and phrases commonly used in this situation include however, therefore, indeed, thus, hence, accordingly, besides, that is, for example, namely, etc. Be sure to include a comma after the introductory word or phrase and before the second sentence:

Some cultures consider the birth of twins to be good luck; however, others regard it as a bad omen.

Our sons have rather different personalities; nevertheless, they are very close.

The last main use of the semicolon is for a series of phrases which contain internal punctuation, usually commas. (And yes, I couldn’t resist sneaking in more colons as well):

My mother-in-law sewed many wonderful things for the boys: their white, traditional christening gowns; little sports coats in their customary colors—one red, one blue; and several Halloween costumes.

Our sons had an interesting assortment of possessions growing up, such as: sturdy, slanted drawing boards; comfortable, black, waterproof boots for playing outside; and a vast collection of Lego blocks.

Once again, this is not mandatory; if the list is unambiguous punctuated with commas, you can do it that way instead:

Our sons had an interesting assortment of possessions growing up, such as: sturdy, slanted drawing boards, comfortable, black, waterproof boots for playing outside, and a vast collection of Lego blocks.

Currently the boys live in separate states and can get together only every few months. Since I can’t reunite them right now, I’m going to at least get the punctuation twins back together. The one remaining similarity between the colon and the semicolon is that they are both placed outside quotation marks and parentheses:

Here’s an interesting fact about the two members of the 80s group The Proclaimers, whose one big hit was “I’m Gonna Be”: they are identical twin brothers.

My mother-in-law sewed many wonderful things for the boys: their white, traditional-style christening gowns; little sports coats in their customary colors (one red, one blue); and several Halloween costumes.

Hopefully this has helped demystify the colon and semicolon at least a little bit—but please feel free to contact me at steph@tightprose.com if you have any questions! They’re really not so daunting, and remember too that a semicolon is usually optional. If you choose to join the ranks of those who don’t use it, you’ll be in good company with writers such as George Orwell and Kurt Vonnegut, to name just…two!

About a week ago, just as some of the coronavirus restrictions began to loosen up here in Florida, my husband and I welcomed a new member of the family:

This is Maddie the Labrador Retriever, who is now ten weeks old, and a real sweetie! My husband and I haven’t had dogs for a while since we’d been moving around, but we’ve trained many puppies over the years. One part of it that came right back to me was how much your tone of voice matters: “Come!” should always be happy and enthusiastic; “No!” always needs to be very emphatic and serious.

So it seems fitting to continue our punctuation survey this time around with two marks that, in addition to being straightforward and easy to use, are important in conveying the writer’s intended tone of his or her words: exclamation points and question marks.

We’re all familiar with both of them. When we were learning to write as children, we probably learned them right after the period; it’s easy to grasp the idea of a marking to convey tone of voice. I’ve always been fascinated with the convention in Spanish, where, in addition to an exclamation point or question mark at the end of the sentence, there’s also an upside-down one at the beginning, so the reader knows right away how the sentence should be read. (By the way, does anyone know if any other languages do that? Just my linguistic curiosity.)

Anyway, let’s start with the exclamation point. Its name tells you exactly how to use it: to mark an exclamation—any kind of utterance that is loaded with strong emotion:

Our new puppy is so cute!

I can’t believe all the toys available for dogs these days!

Just one word of caution when it comes to exclamation points: there has been a growing tendency in the digital age to overuse them, thus robbing them of their punch. It’s an easy habit to fall into—but at least in more formal writing, it’s best to use exclamation points sparingly.

The name of the question mark also speaks for itself: it’s used to indicate a direct question:

Do you like dogs?

How much should I feed my puppy?

You can even use a question mark in the middle of a sentence when embedding a direct question—that is, if the question is in the same form as when it was originally asked. The remainder of the sentence doesn’t need a capital letter:

Is it a good time to get a dog? they wondered.

However, if it’s an indirect question—a paraphrase, in other words—no question mark is necessary:

They wondered whether it was a good time to get a dog.

Besides being indicators of tone of voice, exclamation points and question marks have something else in common: they are both treated the same way when it comes to combining them with quotation marks or parentheses. They are placed inside if they apply to the material inside the quotes or parentheses, but if not, then they go outside. Some examples will make this clearer:

The vet asked, “Has your puppy been sleeping well?”

In this sentence, the material inside the quotes is a question, so the question mark goes inside. Compare to:

Have you read that blog post called “Training Your New Puppy”?

Here, the title of the post is “Training Your New Puppy” (no question mark). The question is whether the reader has read the article, so the question mark goes outside the quotes.

Same goes with parentheses:

Maddie loves her new teddy bear toy. (She never lets it out of her sight!)

The exclamation mark belongs with the second sentence inside the parentheses. But:

Puppies love to chew (maybe because they’re teething)!

Here the exclamation mark emphasizes the whole sentence, but especially the first part of it. The material inside the parentheses is just a speculation on the reason for the chewing and would not by itself require an exclamation mark.

So be on the lookout for interesting uses of exclamation points and question marks “in the wild.” Can you find examples of them inside and outside of quotes and parentheses? Please share your examples below!

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I think Maddie needs to go outside. 😊

When you bring up the subject of grammar, punctuation is probably what most people think of. There’s definitely a popular conception of the “grammar police” as the folks who tell you that you have all your commas in the wrong places.

Yet ironically, most of the time we don’t give punctuation too much thought. At least not until we come across a piece of writing that clearly doesn’t adhere to the norm, such as this excerpt from Ulysses by James Joyce that has…no punctuation whatsoever. When we struggle to make sense of a passage like this, we realize the importance of punctuation, which The Chicago Manual of Style explains well: “to promote ease of reading by clarifying relationships within and between sentences.”

So let’s take a few installments to review the most common punctuation marks. But don’t worry—I’m not going to overwhelm you with every obscure rule from every style manual ever written. (If I did, I’d be writing these posts until the end of time.) We’ll keep Chicago’s wisdom in mind by keeping just to the most commonly used rules, the ones that do most of the work in making texts clear and easily readable.

We’ll start today with arguably the most basic punctuation mark: the period.

I often think of these birds as the period of the avian world. These are Sandhill Cranes, and they’re everywhere in the Florida suburbs. They seem to like nothing more than hanging out in the middle of a street in such a way as to bring traffic to a complete stop (much to drivers’ chagrin).

Likewise, a period signifies a full stop at the end of a sentence:

The Sandhill Cranes don’t seem bothered at all when drivers honk their horns at them.

The drivers, however, are usually boiling over with impatience.

The only time that the placement of periods can get a little confusing is when they’re combined with material inside parentheses. There are two possibilities:

If the words inside the parentheses form a complete sentence—that is, they have a subject (actor) and verb (action)—then the period goes inside the closing parenthesis. Look just a couple of paragraphs back up the page to see an example:

(If I did, I’d be writing these posts until the end of time.)

This is a complete sentence, so the period is inside the parentheses. If, however, the words inside the parentheses do not form a complete sentence, then no period is necessary within the parentheses. There should be only one at the end of the larger sentence. Again, look back up the page for an example:

They seem to like nothing more than hanging out in the middle of a street in such a way as to bring traffic to a complete stop (much to drivers’ chagrin).

This time, the words inside the parentheses do not form a complete sentence because there is no verb (action); the phrase merely elaborates briefly on the drivers’ reaction to the cranes. So the period goes outside the parentheses, at the end of the larger sentence.

The last major use of periods is in forming abbreviations. Did you know that there are different sets of rules about how to use periods in abbreviations? Some style guides, such as Chicago, advocate generally not using periods in abbreviations formed of all capital letters: MD, US, HIV, YMCA, NAFTA, JFK. But there are a few guides that do call for periods in abbreviations such as these: M.D., U.S., H.I.V., etc. So the bottom line is: if you’re writing according to a particular style guide, be sure to follow it. If you’re not using one, it doesn’t really matter which you do—but please pick one way and be consistent. (Personally, I go with no periods, per Chicago rules, since that’s what I’m used to.)

So let’s get some discussion going on this! Please feel free to comment below on any or all of the following:

Today let’s take a break. No writing, no editing, no grammar.

Stop for a few minutes. Forget about everything going on in the world right now. Forget news broadcasts and social media.

Let go of worry.

Take a deep breath and be thankful. We now appreciate that just being able to breathe is a precious gift. So take a moment to breathe.

Breathe again. Think of your family and friends. Enjoy the company of those you’re with. Be thankful also for those not with you. In a little while, give them a call or drop them a line.

Breathe again. Think of your home. It might seem like a prison at the moment, but now more than ever it’s your safe place. Your home is truly your castle now, its walls protecting you and your family.

Breathe again. Think of all those fighting the scourge: doctors, nurses, first responders, scientists, and so many others behind the scenes. Remember that everyone is doing the best they can with the resources they have.

Breathe again. Think of the future. Think of what you’ll do once this crisis is over. Think of how much you’ll appreciate freedom once you get it back.

Breathe again. And just keep breathing. Every day, every hour, every minute until this is all over—we’ll get there one breath at a time.

As we’ve seen in our past few installments, myths, both grammatical and otherwise, often arise from misunderstandings or incomplete information. This is certainly true of the current situation surrounding the novel coronavirus. Because there are gaps in our knowledge about this new virus, there is a lot of confusion, which has in turn led to a lot of myths.

Many of you are no doubt familiar with the fact-checking website Snopes. Of the top 50 trending claims they have recently investigated, only 12 are not related to the coronavirus. Some of the more interesting ones include several supposed predictions of the outbreak in various books or media; a method to check yourself for infection by holding your breath; and the allegation that Corona beer sales have suffered because some people believe that the beer is connected to the virus.

Our grammar myth for today also comes from incomplete information and confusion. I’d bet that many of you (like me) were taught in school not to begin sentences with conjunctions. These are the little words that are used to link words, clauses (parts of sentences), and even complete sentences: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, and so. According to the spurious “rule,” the second sentence in each of these examples is incorrect (the conjunction is underlined):

I looked everywhere for toilet paper, with no luck. And my neighbor said that the grocery store was out of disinfectant wipes.

There are many cases of COVID-19 in the New York metropolitan area, so it is locked down very tightly. But here in Florida, restrictions vary county by county.

Start looking for this and you’ll find it everywhere, because . . . there’s absolutely nothing wrong with it. Look back at what I said above about conjunctions: they are words that link other words, clauses, and even complete sentences. That’s a paraphrase of the guidance in The Chicago Manual of Style, one of the most respected and widely used style guides in the English-speaking world. And other style guides that I consulted agree.

Notice in the examples that using a conjunction at the beginning of the second sentence can be an effective way to create a smooth transition. In the first example, the second sentence starting with And amplifies the first. The use of But in the second example emphasizes the contrast between the sentences. If you were to make either example into one sentence, it would be very long and cumbersome—what is sometimes called a run-on sentence.

So why were we taught not to do this? One of the most popular explanations I’ve encountered in my research is that teachers use it as an easy way to keep students from writing sentence fragments, which lack either a subject (an actor) or a verb (an action), and could look something like this:

When the lockdown is over, I want to go to out to eat. And to the beach.

The second sentence here is not a sentence at all, but a fragment, because it contains no verb. A corrected version would be:

When the lockdown is over, I want to go out to eat and to the beach.

Once I learned as an adult that using conjunctions at the beginning of sentences is OK, it became one of my favorite transition devices. You might have noticed this in my previous posts, so I’ve decided to make this a contest! Count the sentences in this post and in the previous two (St. Patrick, Snakes, and Split Infinitives; Busting Grammar Myths) that start with the conjunctions for, and, nor, but, or, yet, and so. Drop me an email at steph@tightprose.com by April 10 with your total to enter. And yes, there’s a prize—a copy of The Sense of Style, a fabulous book on writing and English usage. The winner will be announced on April 14!

I hope everyone is doing well—stay healthy and safe!

Even if you’re not of Irish ancestry, I’m sure you’ve heard the legend that there are no snakes in Ireland because St. Patrick drove them out. Although my husband swears that his great-great-great-grandfather helped the saint with this chore, the story is just that—a story. There have been no snakes in Ireland since the last Ice Age.

Legends and myths abound in all aspects of life, including grammar, so last time around we set out on a mission to explode some of the most common ones. You might remember “rules” that you learned in school but maybe haven’t thought about in years. Turns out a lot of them aren’t hard and fast laws; they’re more like guidelines. Today let’s look at the spurious prohibition against splitting infinitives.

First of all, what’s an infinitive? It’s simply the word to plus a verb (action word): to love; to write; to play, etc. In grammatical terms, it is the uninflected form of the verb—that is, it describes the action itself. In these examples, I’ve underlined it:

I’d like to go to the pub for green beer tonight.

St. Patrick used a shamrock to illustrate the theological concept of the Holy Trinity.

So far, so good. The problem can come up when we want to add some sort of descriptor to the infinitive. If you put that description word or words between the to and the verb, that is a split infinitive:

The attendance at this year’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade is expected to more than double.

Some scholars continue to adamantly maintain that St. Patrick had no role in the conversion of Ireland.

There is no way to rewrite the first example to unsplit the infinitive without it sounding strange: The attendance at this year’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade is expected more than to double.

In the second example, you could move adamantly: Some scholars continue adamantly to maintain…–but that could make it unclear whether adamantly goes with continue or maintain. Or you could go with Some scholars continue to maintain adamantly… That’s not bad, but adamantly has a lot more punch when it comes right before maintain, doesn’t it?

So these are some cases in which you might want to preserve a split infinitive—and again, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with doing that.

But getting back to legends and myths: one of the reasons they stand the test of time is that they usually contain at least a kernel of truth. In the case of St. Patrick and the snakes, many historians agree that the story is likely an allegory for the saint’s success in removing what was considered an evil—paganism, represented by the snakes—from Ireland.

The kernel of truth in the “rule” about infinitives is that, even though you can split them, it’s not always a good idea. As with many other topics we’ve covered, such as the use of adjectives and adverbs, you should think carefully about exactly what you want to say, as well as the style and tone of your writing. In more formal writing, it’s generally better to not split infinitives if possible. (See what I just did there?

Fortunately, in some cases keeping the infinitive unsplit turns out to be the better option. Here’s a sentence with a split infinitive:

Some people of Irish ancestry are searching for ways to more authentically celebrate St. Patrick’s Day.

And with the infinitive unsplit:

Some people of Irish ancestry are searching for ways to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day more authentically.

Fixing this split infinitive makes for a better sentence because in the original there’s a lot of distance between to and celebrate. Moving more authentically to the end also highlights it more, because the end of a sentence is the position that gets the most emphasis.

Sometimes it just comes down to a matter of which way sounds more natural. Imagine a mother saying this to her teenage daughter on the morning of March 18th, after the latter discovered that some drugstore hair color was not quite as temporary as she had thought:

I told you not to dye your hair green.

That just sounds better than I told you to not dye your hair green, doesn’t it?

So be on the lookout for split infinitives in the wild, and please feel free to comment below with your thoughts on whether they were used effectively!

And no matter your ancestry, happy St. Patrick’s Day! (But no green hair for me, thanks.)

When our twin sons were growing up, they loved the TV show MythBusters. If you never had a chance to see it, the show tested popular urban legends, such as claims that pirates wore eye patches in order to keep their night vision, or that two colliding bullets could fuse together. The other resident guy in our house, my husband, also became an immediate fan. I have to admit, though, that after just an episode or two, I too was hooked. I don’t know if it was due to my latent tomboy tendencies, or just the reality of being the only female awash in a sea of testosterone. At any rate, the show was educational but also very entertaining, and of course all three of my guys particularly enjoyed the experiments involving explosions.

Regrettably, MythBusters is no longer producing new episodes, at least not as far as I can tell from my research. (If anyone has information to the contrary, I’d love to know!) But I’d like to offer a tribute with a series of articles dedicated to grammatical mythbusting: exploding so-called “rules” that in fact . . . are not.

In our last installment, we talked about avoiding the overuse of prepositional phrases, so looking at another issue involving prepositions seems like a good place to start. Our grammar myth to bust today is the injunction against ending a sentence with a preposition (at, by, of, on, to, about, before, after, behind, during, for, from, in, over, under, with, etc.). So, supposedly, you shouldn’t say, and especially not write, sentences such as:

What are you looking at?

John is the person I came with.

British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill allegedly dismissed this spurious rule as “nonsense up with which I will not put.” Alas, Churchill’s quote is also a myth, but it effectively demonstrates why there is no solid basis for this rule: slavish adherence to it results in sentences that don’t reflect how English is actually used.

There are two situations that can result in a preposition at the end of a sentence. One is the use of what is sometimes called a phrasal verb–one that combines with another word or two, usually prepositions, to create a meaning different from that of the verb alone. Some common examples are: ask out; add up to; back up; break down; check in; come across; pull off…you get the idea, and I’m sure you could come up with many more of your own. Churchill’s quote-that-wasn’t contains one of these: put up with, meaning “to tolerate”—and the rearrangement of this phrasal verb is what gives the quip its humorous twist.

Consider the following. If you wanted to rewrite these so that they didn’t end with prepositions, you’d have to do a bit of reworking, which could affect a nuance you might want to express:

While you’re on the way, could you please pick me up?

You can always count on Jane to back you up.

Sharon is hoping that David will ask her out.

In the other situation, however, a preposition has indeed been separated from the word that would ordinarily come after it (its object). Our first examples above fall into this category:

What are you looking at?

John is the person (whom) I came with.

These could be rewritten, putting the preposition and its object back together—notice how in the second sentence we have to add whom to serve as the object, which is why I added it to the original in parentheses:

At what are you looking?

John is the person with whom I came.

How do those rewrites sound compared to the originals? Don’t they sound more formal? So this is something to consider. Yes, you can end sentences with prepositions—but always give them a second look to be sure that it’s appropriate to the style and tone of your writing. When in doubt, it’s always better to err on the side of being too formal. And if you’re not sure whether you have a phrasal verb, here’s a list of 200 of them!

So, aren’t you relieved that this is one “rule” that you don’t have to worry much about anymore? Please feel free to comment below about any other grammar myths that you think need busting!

February is upon us, and in most of the U.S., the month brings with it the worst weather of the year. The combination of snow, ice, and fog unfortunately often result in major traffic accidents, such as a 200-vehicle pile-up in Michigan in January, 2005–one of the worst in recent U.S. history. Incidents of this scope obviously cause major disruptions; highways are usually closed for hours, if not days, depending on the extent of the damage.

Although not nearly as disastrous, pile-ups in your writing can also obstruct your reader’s way through your message. What am I talking about?–a phenomenon sometimes called prepositional pile-up.

First of all, let’s look at what a preposition is: one of those little words such as at, by, of, on, to, about, before, after, behind, during, for, from, in, over, under, and with that are followed by at least one other word, usually more. These prepositional phrases describe location, time, how the actor performs the action described in the sentence (i.e., an adverbial phrase), and so on.

Some examples:

On the highway, behind a truck (location); in the morning, during a snowstorm (time); with great care, in a hurry (adverb, describing how an action was done).

So prepositional phrases can be useful in rounding out a complete picture of what’s going on. The problem comes in when there are too many of them too close together, like cars in a pile-up:

All of the trucks on the highway during the storm pulled off the road due to high winds from the east.

That’s six prepositional phrases in one sentence! Contrast that with the advice given in the Chicago Manual of Style (my favorite style manual!), which recommends using just one preposition per every 10-15 words. Why? Because too many prepositional phrases can obscure the main idea of the sentence. Come to think of it, what was the point of that example again? Oh, yeah, trucks pulled off the road because the weather was bad.

Additionally, when you read a sentence with many prepositional phrases aloud, it can take on a sing-songy quality that distracts listeners from the point. Read the above out loud to try it out. Didn’t your voice fall into a kind of rhythm, something like DA-da-da DA-da-da DA-da-da…?

So how could we rewrite this sentence? Take the main idea:

Trucks pulled off the road because the weather was bad.

Then add the ideas in the prepositional phrases back in, but using other words:

Every truck traveling the highway pulled off the road because of the storm’s strong easterly winds.

So now we have:

We still have two prepositional phrases–off the road and because of the storm’s strong easterly winds–over the course of 18 words, so we haven’t quite met Chicago’s ideal, but I think you’ll agree that it’s much easier to quickly grasp the main idea in this version.

So this time around I have a challenge for you! Be on the lookout for prepositional pile-ups, and see if you can top my example with six in one sentence. If you can’t find any “in the wild,” try making some up. After finding or inventing your pile-ups, try rewriting them – can you reach the goal of just one preposition in 10-15 words? Please comment below and let me know how you do!